Africa’s Oldest Tradition: Fermentation

It is morning in Bolgatanga, the roosters have made their daily announcements at the break of dawn. I am on the rooftop of the Tongo house to watch the sunrise. I see the cows marching in front of the house to the pond, and sister Amina is feeding the guinea fowls, roosters, and hens with local corn and worms from cow dung. It is the second day of Taste of Bolgatanga, and across me, the women have already started the fire to begin our list of cooking activities. I see them from the rooftop, I yell, Bulika (good morning in farafara), then I proceed to also say Toma Toma, a very important greeting to those working, I wave at them with a large grin on my face, and they respond with Naaba (we affirm each other’s presence).

To be honest, it was not until Taste of Bolgatanga that I actually started to pay attention to the delicate food processes of ancestral African cooking, food storage, and food processes. Such as, the pounding of dried peppers in the wooden mortar and pestle to preserve the flavour, the grinding of grains with traditional grinding stones, and delicate use of the clay pot (asanka) and wooden handle (tapoli) to crush fresh vegetables as you would use a blender.

When it comes to Taste of Bolgatanga, I am always moved by the way the women come together to cook, like perfectly arranged lyrics to a favorite song. There is the woman who knows how best to beat the bean mixture for the koose (bean fritter), the one who fries maasa (millet pancakes) in shea butter until the edges are crisps (but not burnt) and the inside is soft, and then there is Mama Hawa, who works so seamlessly in charge, telling each woman when to add water, salt, or mix ingredients together. Mama Hawa’s timing for cooking each food is elegantly perfect.

Meanwhile, the kooko (millet porridge), pito (sorghum beverage), and dawadawa (locust beans) are fermenting in the distance, somewhere in one of the rooms boarded by clay walls, and a thatched roof. Fermentation is an important part of African foods, from Mali to Namibia, from Senegal to Kenya, from Ghana to South Africa, fermentation is an ancestral African food practice tracing all the way to when our ancestors started to collect and store food.

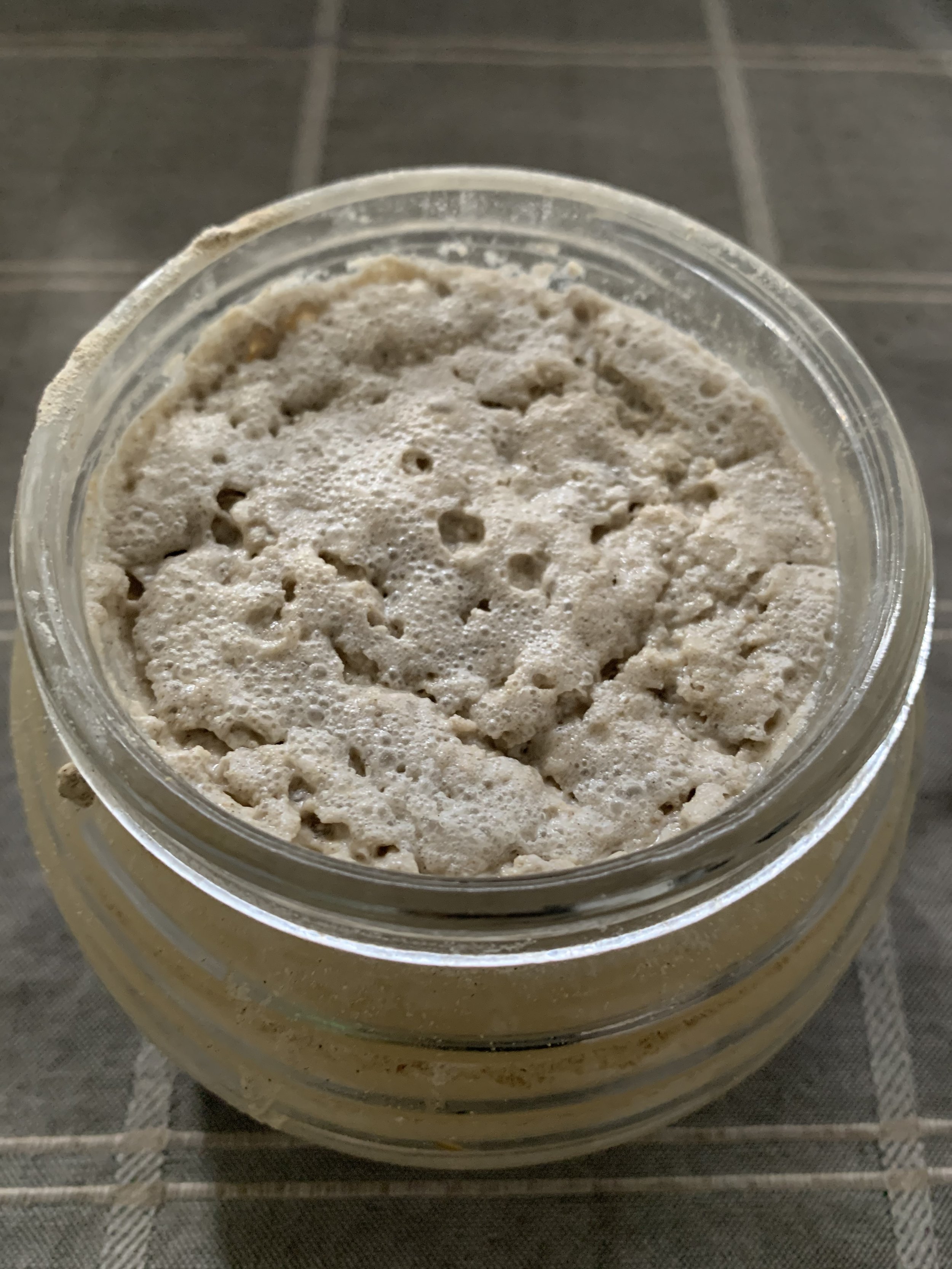

Pito (fermented sorghum drink) at Taste of Bolgatanga

Most staple foods are fermented, from the Ivorians beloved Attieke to Ghana’s Kenkey and Banku, Nigeria’s Ogi, Iru, and Gari to Ethiopia’s njera. Under the Shea tree, in front of one of the Tongo houses, Mama Hawa explains the fermentation process. Depending on the food, she says, once the grains have been washed, they are soaked overnight. The next day, the soaked millet is spread on a tarp on the floor for three days. Each morning and evening for three days, water is sprinkled on the millet so it can sprout. Once the millet sprouts, the grains can be dried for a day. I listen keenly as she speaks, taking notes and jotting down the process, knowing that each fermentation method and process is different, depending on the food, culture, ethnic group, and traditional beliefs.

The traditional fermentation process are methods passed down from the previous generation. Madam Abugre, who facilitates the dawadawa teaching for Taste of Bolga, when I once asked her how she knew to ferment dawadawa, she said it was her mother who taught her. Then I asked her, who taught her mother, and she said it was passed on from her grandmother, and so on. Traditional African way of fermenting foods is a cultural language embedded in a relationship between women, the land, lineage, traditional tools, and heritage.

Fermentation preserves the nutritional and sensory qualities, enables the extension of shelf life, enhances the intake of nutrition and vitamins, and provides a variety of ways to digest grains. Fermentation minimizes the chances of food spoilage in tropical climate conditions. The abundance of probiotics in fermented foods is great for improving digestion in preventing and treating diarrhea. In addition, fermentation also helps in preventing tooth decay, as well as, the management of diabetes. Fermented foods are a wealthy source of nutrients, they are powerful in removing allergens, building a healthy gut microbiome, and eliminating toxins.

fermented millet water for Tuo Zaafi (TZ)

As I listen sharply, Mama Hawa tells me that some foods need to be wet then milled for the fermentation process to begin, this also removes anti-nutritive or toxic compounds. Tubers such as cassava are peeled, washed, and fermented for three to five days and milled into granulated flakes like couscous to make attieke and gari. During the process, undesired compounds are removed and antimicrobal, antifungal, and vitamins are formed. Biochemical and nutritional changes occur during the fermentation. Fermented foods, among other ancestral ways of living, have kept many African people healthy. Fermented foods are cultural, scientific, historical, and environmental.

In Western nutrition, most practitioners say that all diseases start from the gut. In this case, our African ancestors were ahead of their time. The gut microbiome is gaining ground as an important place to start to improve human health. On the last day of Taste of Bolga, when we drink Pito (fermented sorghum), the taste always reminds me of kombucha, the now widely popular fermented tea, its global branding and reach. I think about the possibilities of fermented African foods, and how food science can learn from the knowledge, the practice, the process, and the wisdom of African fermented foods.